My grandparents were both born in the 1920’s South where racism ran and currently still runs rampant in the streets and institutions of what is falsely called “The land of the free and the home of the brave.” And yet here we are, in 2020, still talking about racism in America.

I do not have to tell you nor remind you of what ails America, nor do I have to remind you of the protests, the verdicts, the unrest. But what I do want to point out is that all of the aforementioned occurrences are sheer reactions to a broken justice system. Now our system, the educational system is just as broken. It may not be causing bodily harm to our students, but we, the educators, the leaders of this campus have said something, assigned an assignment or exam, or implemented a process/procedure that has created institutional barriers which prohibit our students from being their magnificent selves in the classroom, therefore truncating their growth and development as young men and women. We need to fix that; we need to fix us; we need to fix our classrooms. We need to fight for educational freedom. We need to change!

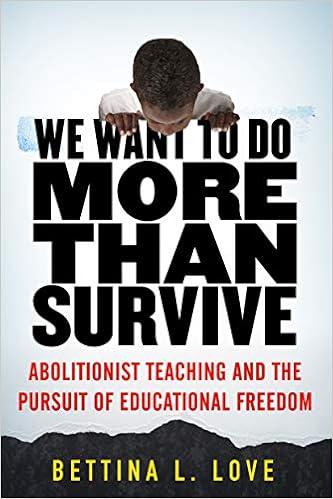

Bettina Love in her book, We Want to do More than Survive: Abolitionist Teaching and the Pursuit of Educational Freedom defines abolitionist teaching as “choosing to engage in the struggle for educational justice knowing that you have the ability and human right to refuse oppression and refuse to oppress others, mainly your student” (11). She goes even further as to claim “Abolitionist teaching asks educators to acknowledge and accept America and its politics as anti-Black, racist, discriminatory, and unjust and to be in solidarity with dark folx and poor folx fighting for their humanity and fighting to move beyond surviving” (12). I want to point out that Love is calling all of us as educators to become abolitionists and set the minds of our students free in order to thrive and not merely survive. This will in turn set their bodies free – free to bring their full authentic selves to the classroom and to discussions in class. The great abolitionists both recognized and not put their lives on the line to ensure that those who were enslaved both mentally and physically were freed from a system that sought to hold them captive for the rest of their lives and the rest of the lives of generations after them. And we need to be emboldened and empowered to liberate our students from unclear graduation pathways, unclear and unrealistic assignment/exam requirements, antiquated classroom pedagogy and methodologies, and faculty and staff who make generalizations and tiny racist comments of our colleagues. We can make the change!

It is quite evident from the verdicts in the courts, the protests in the streets, the bodies in the streets that we have not been freed from the institution of racism that has plagued this country from its founding. It is evident when we continue to teach material in class that is not representative of our minority majority serving campus. It is evident when we facilitate discussions in class that empower and embolden the oppressive viewpoints of a few while harming the many. I know some of you who are reading this belong to ally groups both visible and invisible, and I thank you because we need your voices, support, and love. I know some of you belong to task forces, working groups, councils, and other leadership positions that are trying to work to see some of these systems dismantled and replaced with good meaning policies and procedures. So please, keep working, keep pushing, keep fighting. But have we seen anything change? Any real change? Any long lasting change? Love puts it best when she says “[We] must move beyond feel-good language and gimmicks to help educators understand and recognize America and its schools as spaces of Whiteness, White rage, and White supremacy, all of which function to terrorize students of color” (13). If you disagree with that sentence, I beg you to really listen to the responses of our colleagues as they respond to discussions of racism and students of color in meetings and FLEX sessions. Read between the lines of what is not written in email threads. Read what is on their syllabi. Look at the work that has not been done.

As a campus, department, discipline, and district, now is our time to show our students and the students after them, and the students after them that they matter. We have the people in place, the money in place, the training in place to really transform RCC in the name of Educational Social Justice. We can do it, so lets do it!

I leave you with these questions as we start thinking about Ant-Racist Practices and Pedagogy:

- Is there racism in the educational system?

- What is your definition of Anti- racist teaching or abolitionist teaching?

- Do you take into consideration students’ race or even your own when you enter a classroom?

- Why would educators be resistant to making changes in order to implement culturally relevant texts and pedagogy?

- Why are we still talking about race and racism in 2020?

- Bonus question (do not respond in blog). What are some biases, prejudices, preferences, fears that you’ve had to admit you have as you’ve worked with faculty, staff, and students?

This is Part 1 of a post on anti-racist teaching practices. To read Part 2, click here.