Would you be surprised if I told you I had a hard time sitting down to write this blog post? Grading, or even just talking about grading, is not really at the top of my list right now. But, even in the best of scenarios – wearing real pants, drinking nice coffee, in a clean and dedicated workspace, and all caught up on grading except for those fresh stacks of essays – I would likely still procrasti-do-all-the-laundry-and-hey-might-as-well-darn-these-socks-while-I’m-at-it-amirite before I spilt ink on that first paper. Now, it’s an even greater struggle as we manage the changes in our own home lives while troubleshooting technology for ourselves and with our classes, trying to keep and motivate our students, and worrying how everyone is dealing with everything outside of the classroom, too.

And yet, as ever, the work of grading essays looms. But as much as I have to cajole myself into diving into a new pile of papers, I’d be lying if I said it was all drudgery. I have definitely silently or not-so-silently raised the roof at my desk when I read a student’s insightful observation about an enjambed line, when I could tell in a final draft that the student was really paying attention to that lesson on quotation sandwiches, when the parenthetical citations were pristine and even that hanging indent was on point! In these best, quiet grading moments, we see our students, and we get a chance to tell them what we saw – the work that still remains, sure, but also the work they did to understand that difficult concept, the effort they put in to make sure that everything looked just right, the thinking and growing and learning that is still in progress. While grading may literally be putting grades on papers and in gradebooks, the process is and means more than that. Ken Bain in What the Best College Teachers Do puts it this way: “[G]rading becomes not a means to rank but a way to communicate with students” (153). Many things have changed very quickly this term, but the grading, more or less as we have always known it (give or take a learning management system), is still there, both as a means of touching base with our students and communicating our reactions and expectations, and as very real labor.

Corresponding with the team about how to handle this topic, it became clear that we needed and wanted to explore not just ways of managing the important work of grading generally, but ways of thinking about how to handle our grading load in this strange and stressful time specifically. First, how can we more efficiently do the grading that we need and often actually want to do? What tips, what strategies, what grading hacks? And, looking at the last half of the semester, what can we do to rethink or reconfigure our plans to make the space to be more kind and forgiving to ourselves? As we’re working so hard to be flexible with our students, are we also being flexible with ourselves, our plans, our expectations?

Grading Hacks

The Internet is full of articles about how to grade more efficiently – “Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half”! “How to Escape Grading Jail”! Let me summarize the literature for you – you can do lots of different things, some things with technology or some things without technology, and not all of these things will work for all of us, but there are many things to try. The advice is diverse and general, and while I will offer some suggestions and direct you to some sites below, what really interests me is what you all are doing to adapt your grading practice to this particular moment (leave your best grading tips for us below in the comment section!).

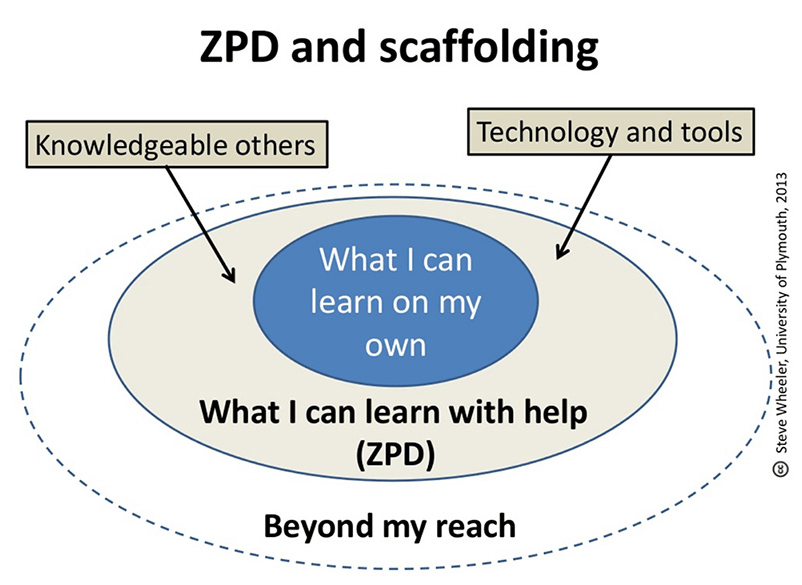

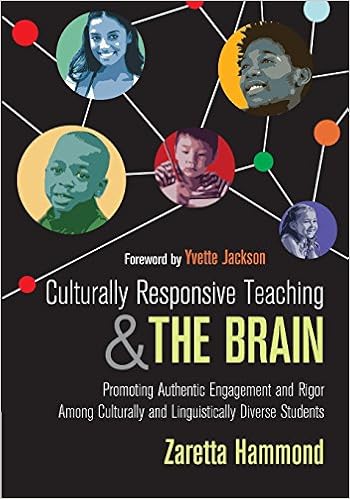

One author, Nicki Litherland Baker, has an interesting take if only because it helps us see our grading work in another light. In an article titled “‘Get it off my stack’: Teachers’ Tools for Grading Papers,” Baker uses something called activity theory to observe that “teachers’ comments follow predictable conventions, making feedback a specific genre” (40). In this formulation, the work of grading is essentially writing, so as grader-writers we need to approach it in the same ways we encourage our students through their own processes – by breaking it up into manageable chunks, by forcing ourselves to begin and put time in even on days we’re not feeling particularly inspired, and by motivating ourselves with intrinsic and extrinsic rewards (43). Sometimes we can forget how much like our students we are! Especially now, when there are lots of other important things on our minds, we have to think about how we can scaffold our process to set ourselves up for success. So what can we do?

Embrace what technology can do. Technology is hard. A couple of times a day, any given day, I get an email from a student about a link that’s not working, an assignment that is locked, or a slow ConferZoom connection. But for all the tech issues we have to navigate, there are unique things that we can do online. In my discussion boards, I ask my students to respond to a prompt and then ask them to reply to one of their classmates’ insights, and I often give them the choice of responding with text, or with a meme or GIF (one of many great ideas from Flower Darby, co-author of Small Teaching Online). I miss seeing my students’ facial expressions and reactions in the classroom, but a well-chosen GIF or meme is worth a thousand words. It’s also really easy to grade — if they left a meme, I know they’ve been back to the discussion board and are keeping an eye on the conversation.

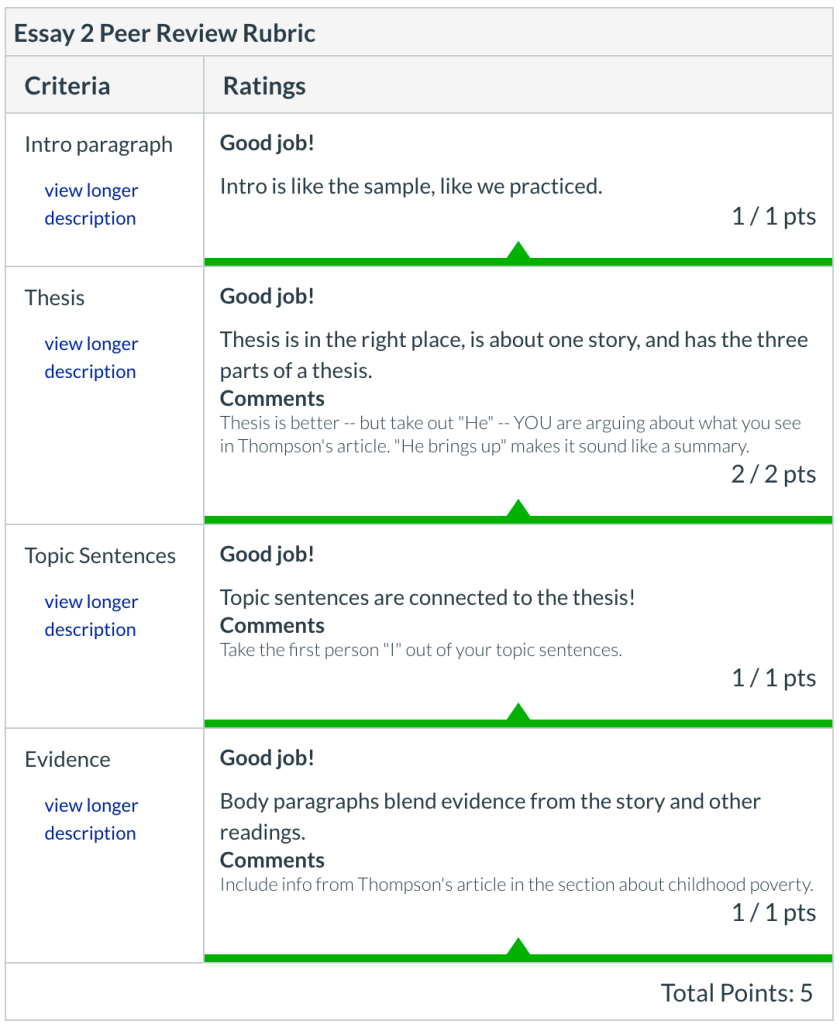

Canvas has a lot of time-saving and grading-specific capabilities already built in, too. You can, for instance, set up your gradebook to drop the lowest quiz score, leave audio feedback in the same place you leave a written comment, and, when you’re grading an assignment, you can directly message students who haven’t submitted without leaving your gradebook. It also has a rubric feature to help you grade assignments more efficiently. I started using Canvas rubrics more this year and though it takes time to set them up, they do help me stay focused while grading. I like that I can put my own words into them so the comments really sound like me and that I can still add comments if I need to/cannot help it, but if I set up my rubric well enough in the beginning, I often don’t need to add anything else. I also like that students can use the same rubric to evaluate each other’s work during peer review so there are no surprises about what we’re looking for. Being really clear with myself and students about expectations also cuts down on the grading time.

And no matter what you’re using to provide feedback on essays (Canvas, Turnitin, Word, GoogleDocs), you can create a “commenting library” where you can save time by keeping your most common notes to copy and paste alongside helpful links/resources you can connect your students to directly. At the end of this post, you’ll find a few links about these Canvas grading options that you might try out to make your grading more efficient.

Get by with a little help from your friends. One colleague, now retired, used to email gems she found while grading – fun and funny sentences that she encountered in student work. These emails made the often very solitary work of grading feel a little less so, and put a little pep in my grading step. Email/text/zoom (if you aren’t zoomed out) your teacher and writer and grammar friends when you’re making your way through a stack. Better yet, treat it like an extrinsic reward – grade 5 papers, and then take a break and have a 2-minute virtual dance party with your work besties.

And you know who else you can share this work with? Your students. Bain writes that “some of the best professors ask students to assess themselves. One frequently used model requests that they provide evidence and conclusion about the nature of their learning” (163). While it is not feasible for every assignment, I think this type of reflective assignment could be especially valuable in this context, a space for students to think about what they have overcome and what they have accomplished under extraordinary circumstances.

Don’t sweat the small stuff. We’re living and working through a pandemic. Give everyone some slack, including yourself. This can take on different forms. It might mean prioritizing some grading over others. In her comment to this post, for instance, Janelle shares how she gives automatic points for a draft turned in, but also gives constant feedback throughout the writing process – assigning points quickly to be able to spend more time commenting and communicating meaningfully. For me, not sweating the small things means adopting “Okay” as a mantra. You need an extension? Okay. You forgot to document that required source and want to fix it now? Okay. You mean, dear student, that you recognized the work that needed to be done and are actually trying to do it and turn it in to me? Okay! At the end of the day, especially if the assignment is still in my grading queue or in progress, especially during a pandemic, I say “okay,” and move on to the eleventy billion other things I have to do without agonizing over it. Bain observes that flexing “power over grades” through deadlines might just be counterproductive to learning (154). He isn’t saying to get rid of deadlines altogether, but rather to evaluate whether our attitudes and policies and practices actually facilitate learning.

Grading Flexibility: “Triage”

At Academic Senate this week, during a roundtable on the college’s approach to COVID-19, one word that came up often was “triage.” The college has been sorting through the problems and concerns and addressing the most pressing needs first. In the week we shifted to teaching online, I know that many of us triaged our own work. We stopped what we were doing to learn the technology, help situate our students, and put together a module or two before even thinking about grading again. Now that we’re at mid-term, maybe it’s worth pausing to take stock, to see if there are any adjustments we might make to give us a little more space to breathe.

Bain gives us what I think is some good criteria for grading triage in a chapter looking at how the best college professors approach grading, or assessment, and evaluation. The most outstanding teachers, Bain tells us, take a “learning-based approach” instead of a “performance-based” one. In the latter, “students’ grades come primarily from their ability to comply with the dictates of the course,” but in the former, the professor asks a fundamental question: “What kind of intellectual and personal development do I want my students to enjoy in this class, and what evidence might I collect about the nature and progress of their development?” (152-53). For triage, while keeping CORs and SLOs in mind, we might ask questions like: Do I have any assignments lined up that are performance-based, and what can I do to make them more learning-based? Where are my students now in terms of SLOs? What assignments would best serve the goals of the class and my students’ learning, right now? How can I make assignments that are high value for student learning but easier on the grading? What assignments will give me the best opportunities to communicate with my students about how to move forward?

Discussion Questions

- How do you communicate with your students through grading? How can you make sure you’re being compassionate and constructive while being efficient?

- What are your best grading strategies? What are your grading hacks? What keeps you motivated through those stacks of essays?

- What grading triage, if any, have you done, or thinking of doing?

- How have you been flexible with yourself in terms of your plans or expectations for the semester? Where might you be more flexible?

- What are your best examples of learning-based assessments?

Thoughts? Join the discussion below. And we hope you’ll join us for a virtual meeting during college hour on April 30!

Some Helpful Resources

- Canvas Instructor Guide: SpeedGrader

- Canvas New Gradebook Best Practices

- 6 Canvas Hacks for the Happy Grader

Resources from the Workshop on Zoom

Download

Here’s the article we mentioned at the beginning: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/dont-care-about-work-coronavirus_l_5ea0aa73c5b69150246ce525